Git and GitHub

Introduction

Git and GitHub are two tools that work together, but it is important to understand what each does and how they are different to each other.

Here are some basic things to know:

Git is a stand-alone version control system that runs from the command-line on a variety of platforms, including Linux, MacOS, and Windows.

GitHub is a cloud-based Git repository hosting service that makes it easy to use Git for version control, collaboration, and sharing code. This service is offered through a website.

There are other Git hosting services out there, including GitLab, an open source tool that can be installed on a local server.

GitHub (and services like it) builds on top of Git, adding some functionality to it, while Git can interact with GitHub through actions like cloning, pushing, and pulling. For example, Git does not have a fork command. GitHub (and other hosting services such as GitLab) have added this command as a convenient way to copy repositories.

Using Git and GitHub Together

In practice, although Git does not require GitHub, we tend to use Git and GitHub together.

We use Git to perform version control on our code, and we use GitHub to share code and to collaborate on coding projects.

When we use Git and GitHub together, we typically follow patterns.

For example, a basic series of actions one continually makes with Git are the following:

| Action | Description | Command |

|---|---|---|

| Fork | Forking a repo makes a copy of someone else’s repo in your GitHub account, which you can now modify. Note: Forking does not have to be performed if you are not interested in altering the code. You can clone it directly. | This is done through GitHub’s web interface by clicking on the Fork button. |

| Clone | Cloning the repo to a workspace to which you have access, whether a local machine or a remote resource (e.g. Rivanna). | git clone <repo> |

| Add | Creating or editing a file locally and then adding it to the list of files git will keep track of. | git add <filename>Note that you may use wildcards here, e.g. *, to add more than one file at a time. |

| Commit | Committing the changes made to the file by adding them to the repo’s database of changes. This is accompanied by a brief, descriptive message of the changes made. | git commit -m "What you did" |

| Push | Pushing the changes to the remote repo that you cloned from. This uploads both the files and the database changes to the repo. | git push |

| Pull | Pulling, i.e. downloading, any changes that have been made to the remote repo to your local repo. This usually happens if you are working in teams on the same project. | git pull |

| Pull Request | This is a request made to the owner of the original repo to pull in the changes you’ve made to your forked copy. | This is done through GitHub’s web interface. Read the docs.  |

| Fetch Upstream | This refreshes the content of your forked repo with the content from the original repo. | This is done through GitHub’s web interface. Read the docs.  |

This is not the only pattern to use with Git. Here is another — the Git Fork-Branch-Pull Workflow

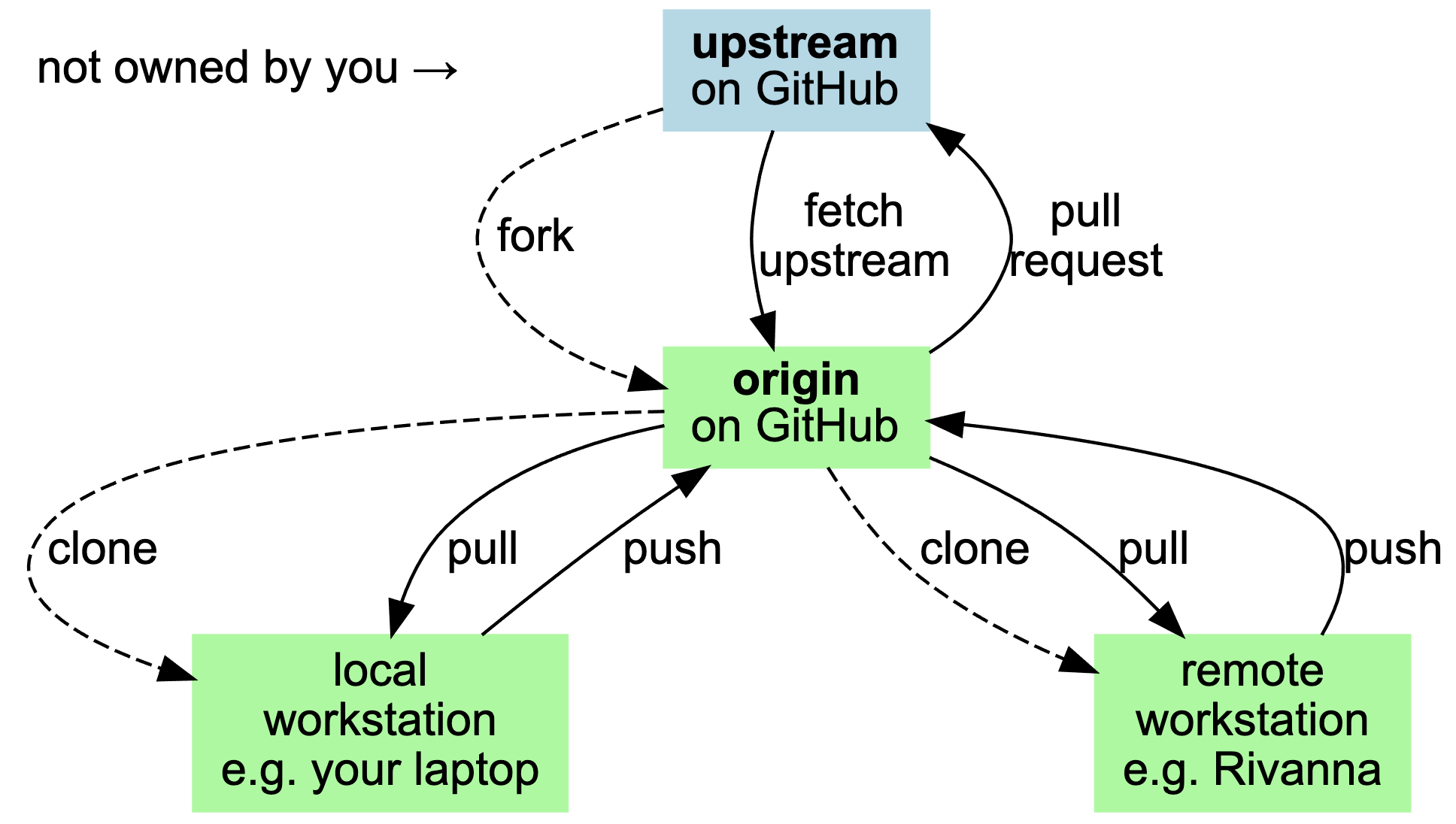

Here is a visualization of the process:

In this diagram, the dashed lines refer to actions performed only once for a given repo.

Forking and cloning are done once to acquire a repo.

Fetch upstream (aka sync fork) and pull requests take place on the GitHub server.

Pull and push on your local machine are done repeatedly as you develop and share code.

Note that the here the expression “remote workstation” may be confusing; it means remote relative to your laptop, e.g. Rivanna, which we sometimes call local relative to the GitHub repo.

In any case, note that these two copies of the same repo do not communicate with each other directly, but rather through their common relationship with the GitHub hosted instance of the repo.

To Learn More

The Git website has excellent learning materials. Use the following links to access videos and tutorials: